Questioning Terroir In Chocolate: When Feelings (And Marketing) Get In The Way Of Accuracy

“Ultimately, does terroir matter? For the novice wine drinker or collector, the answer is probably yes. Ensuring that one is drinking, or collecting, those wines perceived as “more important” because they come from a very unique “place” matters a lot to the novice and the collector.

For the seasoned, well-educated wine taster, terroir is less important. A seasoned wine taster is usually looking for value and not cachet. When the two can coalesce, that’s great. The seasoned wine taster is also looking for new experiences to broaden their knowledge and palate. While the seasoned wine tasters can appreciate the value of terroir, it becomes less relevant to determining what they are apt to drink.” - Paul Malagrifa, Certified Wine Educator.

Terroir can be described as the complex of natural environmental factors associated to a specific place (soil, climate, elevation, sunlight intensity, rain, etc.) believed to heavily influence the quality and the flavors of an agricultural product. The concept of terroir was born in the wine world, but the story of this term might not be what you expect.

Terroir has always been a controversial topic in many agricultural products, from wine to cocoa.

In the 18th century, terroir wasn’t associated to prestigious wine bottles, but it was used to describe disgusting ones. “One says that the wine has a taste of terroir when it has some disagreeable quality that comes to it from the nature of the terroir where the vine is planted,” was the definition of terroir in a French dictionary from 1690.

The transition to a positive connotation happened in the 20th century, when the battle of the bottles was in full swing, and grape growers and wine makers felt the need to defend themselves from international competition using terroir as an efficient weapon. For example, when the sparkling wine Champagne reached such an international fame that vintners from all over the world started to produce their own outside France, wine makers from the Champagne region felt the urge to act.

“In 1905, the region’s growers successfully lobbied for the creation of strict rules—the first of many to come—mandating where (and how) wines must be made in order to bear their place of origin. (It’s for this reason that only sparkling wine from Champagne can technically be called “Champagne.”) Growers in Burgundy, also wary of competition and fraud, joined in the early push to valorize terroir, such that by the 1930s one Burgundian folklorist was marketing the region’s wines as a “subtle emanation from the soil” responsible for locals’ “joie de vivre.”

Matthews contends terroir underwent another “dramatic uptick” in usage and prestige after Californian bottles bested some of France’s top wines in the historic 1976 Judgment of Paris. As the French sought to fend off American competitors, they re-emphasized the connection between quality and place in a way that gave France a permanent advantage: New World winemakers could use fine barrels and employ talented vintners, but only Gallic vignerons had France’s exceptional land.” – Bianca Bosker from Food & Wine.

Empty of any solid reason or scientific evidence, terroir started its career as a fancy term solely in the name of business, not agronomy. It was a tool of defense against international competition that advantaged those who first claimed their lands as more prestigious over others.

The fact that the same type of wine could be made hundreds of thousands of miles away, and taste even more exceptional, had the French so preoccupied that they needed to tie their products to their terroir, literally translated to “soil”, so that nobody could ever take their reputation away. It’s from this scenario that the word terroir was taken and used in other food sectors, craft chocolate included.

The use of the word terroir in craft chocolate starts from a beautiful premise: unlike industrial manufacturers, chocolate artisans do their best to respect, preserve and enhance the flavors intrinsic to the cacao they source from different origins. Paying a premium price for the best cacao on the market, each craft chocolate maker highlights the differences between several places on earth where cacao grows.

Although inaccurate and simplistic, saying that “Madagascan cacao is citrusy”, “Ecuadorian cacao is floral” or “Peruvian cacao is fruity” expresses the general intention of craft chocolate makers: when fine cacao is treated with care, consumers can explore a plethora of flavors to be associated with a specific place or a local producer. This goal is commendable, and finally brings the spotlight to the initial segment of the cacao supply chain, where most of the flavors of the chocolate get developed.

Both craft chocolate makers and craft chocolate consumers think that they are celebrating and honoring terroir. The land where the cacao grows is responsible for the amazing flavors delivered in that delicious bite, and should be praised and taken into high consideration. There is only one yet crucial detail that has been always overlooked when talking about terroir in chocolate: what happens at origin is much more than just terroir.

Some chocolate experts and cocoa producers argue that most of the flavors are developed in the fermentation box, and have little to do with terroir.

A lot of what we think is terroir-driven is actually human-driven. Before terroir, there is the accurate choice from the agronomist of a specific cacao variety and genetics to be planted. During terroir, many human actions make sure to take care of the cacao trees with different farming techniques. And after terroir, there are strict fermentation and drying methods that involve an infinite number of variables between times, temperatures, human interactions and type of bacteria.

Some experts like to stretch the concept of “terroir” to also include the post-harvesting processes at origin, but this was not the intention of the term, and intending terroir to include also fermentation and drying practices (human manipulations that have nothing to do with spontaneous natural elements) is too much of a stretch. In the craft chocolate industry, there have been many cases where specific producers’ methods were mistaken for terroir. Let’s take the example of Papua New Guinea.

Any amateur taster at the beginning of her/his journey has tasted chocolate made with cacao from Papua New Guinea, and most likely thought that it was incredibly smoky, sometimes to the point of unpleasantness. This specific tasting note can be thought to belong to the terroir of Papua New Guinea, to be a “gift” of nature that gives such a strong connotation to the cacao from that country. Reality couldn’t be more different: because it rains a lot and sun is short in supply, farmers in Papua New Guinea are known to dry their cacao with wood fires. Here is where the romanticism about terroir falls like a sandcastle since that smoky note has absolutely nothing to do with the land where the cacao grows, but entirely depends on the post-harvesting methods of choice.

The debate is not whether terroir influences the final taste of the chocolate. It definitely does. But HOW MUCH is the misunderstood part. The concept of terroir gets further lost specifically in craft chocolate, where the cacao used rarely comes from one single farm, but it’s a collection of cacaos from different farmers spread in different areas or regions.

Usually a local cacao producer or a cooperative collects cacao from different farmers, whether wet or dry, and brings it all together to be sold (since the small quantities from each farmer rarely allow for single-farm offerings). The cacao that ends up in the same 50kg bag comes from five to a dozen different micro-terroirs. How extended has got to be the concept of terroir to include them all under the same umbrella?

There is also the case of fine cacao producers that plant the same single-variety cacao in different countries (which of course will have different terroirs), and make it taste exactly the same (or better, have the same potential aromatic profile). Not by over-fermenting, over-drying or with some magical techniques, but just by using the same single variety and the same fermentation and drying protocols. All human decisions that seem to make any terroir-effect evaporate. It has been proven endless times how genetics, post-harvesting processes and chocolate making have a solid, huge impact on the final flavors of the chocolate. But terroir?

There isn’t one single research that, given the same cacao variety and post-harvesting processes, prove the association between variants in flavors and variants in soil, climate, elevation, etc. One might argue that weather actually influences the final flavor of the cacao, since cacao from different harvest years might taste different given different weathers. But like in the case of Papua New Guinea, the weather doesn’t influence the flavors inside the cocoa beans per se. Weather influences the choice of what post-harvesting methods to apply, that in return influence the final flavors of the cacao.

Dozens of articles, written by the most admirable professionals in the craft chocolate industry about terroir in chocolate, don’t ever seem to give a plausible explanation. One piece of evidence, one research, one study, one solid motivation that would causally link a specific terroir to the resulting flavors in the chocolate. After questioning the validity of terroir, many craft chocolate products can be reevaluated. Not to attribute them any less value, but to clarify the actual role of terroir in their final flavors.

While I was in Grenada, known as the island of spices, I got to see cocoa trees growing alongside trees of nutmeg, cinnamon and clove. Interestingly, the chocolate made from that cacao always ended up showcasing spicy tasting notes, remarkably similar to those same neighboring trees that surrounded the cacao trees during their growth. With the unquestionable concept of terroir in mind, I always linked those flavors of nutmeg, cinnamon and clove in the chocolate to the influence that those trees had on the cacao produced, like the flavors from the neighboring trees were somehow “transferred” to the cocoa tree.

It is a poetic concept indeed. But now that I challenge the validity of terroir, I wonder if anybody has ever tried to put those same cocoa trees in a different environment (or terroir) to see if, in the absence of those specific surrounding trees, the cacao still retains those specific spicy notes. What if that specific cacao variety already had that spicy aromatic profile, and the surrounding trees had nothing to do with it?

The company Marou Chocolate in Vietnam crafts chocolate starting from the cacao from six different provinces, that is kept separate and used to create single-province chocolate bars, each one expressing a different set of tasting notes. If no further question in asked, this could be the brilliant case of the power of terroir: cacao grown in different places showcases different tasting notes. However, this could be an unconfutable proof only if the cacao cultivated in each province was the same.

Given the same variety (and hypothetically the same post-harvesting methods), terroir would definitely be the biggest variable. But if the cacaos growing spontaneously in each province were already different to begin with, then the different tasting notes would be less likely to come from the variants in terroir, and more from the variants in genetics.

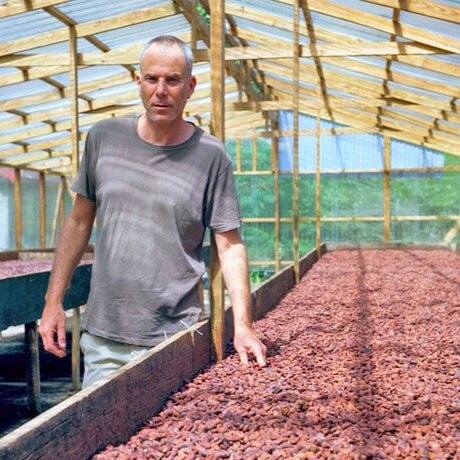

Photo Credit: THE CHOCOLATE BAR

If research and experiments that can prove the validity of terroir are still scarce after centuries, the concept of terroir still retains all its marketing power (maybe precisely because studies on the subject are so scarce). Cacao producers proudly promote the association of some enchanting flavors to the land where they grow their cacao, so that nobody would ever be able to take that market advantage away from them. Further research on the subject is actually not incentivized. Whenever somebody threatens the validity of terroir, the usual collective reaction in the craft chocolate industry is often hostile.

Nobody wants to take the romanticism away from the concept of terroir, and the belief that natural elements have a huge impact on the flavors of the cacao gives producers the right to heavily advertise their land. If the same cacao variety was to be planted in different places with the same results, then its amazing flavors wouldn’t be attached to a specific place, making the producer lose a big marketing tool. The truth is that, even if terroir was real, it would have way less importance in the final flavors of the chocolate compared to the hundreds of other variables involved, from genetics to human and bacteria actions to the countless machines that cacao has to go through before becoming chocolate.

This is one of those cases where terroir doesn’t need sustaining research, but conversely has to be proven wrong for chocolate lovers to stop fantasizing about it.

But whether you want to believe in terroir or not, it’s totally up to you. But as a chocolate consumer, don’t ever let it be a decisive part in your purchasing process, and don’t let anybody convince you that you should like a specific chocolate because of “terroir”, especially when your palate says otherwise and when you have no idea what’s actually happening at origin.